Most of us have found ourself sketching on location, with one hand dedicated to balancing a journal or drawing board and one alternating between applying color, setting down the first brush, then quickly picking up a water brush to create gradations before our color wash dries out. Labor-intensive? Yes. Exhausting? You bet. No other option? Well.... Enter the twin-brush technique.

This is a technique that I was introduced to some time back by a Chinese calligraphy master and quickly found that, with just a little practice, it quickly became second-nature -- and has become such a wonderful time-saver!

To begin with, one brush (hereafter referred to as the "water brush") is cradled horizontally between the fleshy web twixt thumb and index finger, and the crotch between index and middle finger. (Note: this brush will also be behind the vertical ink brush.)

The second ("ink") brush is held vertically in front of the horizontal water brush -- pinned between the tip of your thumb and first joint from the knuckle of the index finger. The tips of the index and middle fingers are on the far side of the vertical brush, while the tips of the ring and little fingers are on its near side. As depicted above, the combination creates a t-shaped arrangement in the hand and is very comfortable to work with.

Once an area of ink has been applied to artwork, the index finger is used to rotate the tip of the horizontal/water brush downward till it is under the tip of the middle finger.

The combined index and middle fingers continue to rotate the water brush down until it is parallel to the vertical ink brush -- with the ink brush still in front of the water brush. The tips of the ring and little fingers move to the far side of the brushes.

The two brushes are now rotated around a vertical axis to reverse their positions, using a counterclockwise side movement of the thumb and index finger. (The water brush is now in front, the ink brush to the rear.)

Next, the tip of the middle finger is slipped beneath the rear/ink brush and are used to rotate the brush upwards to the horizontal position.

Finally, the ring and little fingers are returned to the near side of the vertical/water brush, and the tip of the thumb to the first joint of the index finger. This technique can then repeated as necessary until the sketch is completed.

I've tried to be as specific as possible in the written description, just in case the illustrations are not clear enough on their own. But, just in case the description risks making this technique sound too convoluted, I've also included the 5 second video below. (We are, after all, visual people. Aren't we?) Once you've practiced this technique a few times your hand should feel relaxed and stress-free, with the two brushes in complete harmony.

So, hopefully, you'll find this little "trick of the trade" of interest, and will give it a try. In future articles I'll try to offer additional "tricks" to tickle your fancy and expand your creative options. Thanks again for letting me share with you. Cheers!

PS, if you see, or read about, a particular tool or brand that interests you but is not currently available in your area, please consider visiting my new Art Supplies & Provisions Online page. (You can also find a link in the menu at the top of this blog.) There you will find tools, equipment, media, and supplies that I have tested thoroughly and am happy to recommend highly.

The Art of Traveling with a Sketchbook -- I've been an artist, naturalist, traveler, and adventurer all of my life. I don't always end up where I want to be, but I usually end up where I need to be (and always do a few drawings and paintings along the way.) Want to come along?

Tuesday, August 28, 2012

Friday, August 24, 2012

Zoetropes, Flip Books, Lights, Camera... and Action!

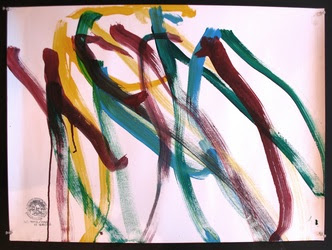

Trying to convey motion in a static image has always fascinated me. For much of my life as a

professional artist I (like many artists before me) have also been intrigued by the dynamic poses found in Hellenistic and Baroque painting and sculpture. Dancers in particular have drawn my attention, as has the creative potential of image sequence.

The earliest successes in capturing motion through the sequencing of still images were achieved in France. And (in 1892) Charles-Emile Reynaud gave the first public screening of an animated movie. The film ran 15 minutes in length and utilized 500 separate images hand-drawn and colored directly onto the clear film stock. (It was also the first time in cinematic history that perforated film was utilized in the projection process.)

In my own work I have sometimes explored the possibilities of the single, stand-alone image,

while, at other times, I have used image series like this -- installed in a long horizontal sequence on a

gallery wall to convey both motion and the passage of time. I've constructed with flip books (which have been popular with artists and the "motion picture" industry since at least 1886) and (with the help of my steampunk wife) even experimented with creating my own animation strips for our 2 zoetropes (first introduced around 1834 -- quite the range during the Victorian era and now regaining popularity among retro and steampunk fans).

In this action sequence, flowing hair, twisting torso, swirling drapery, swinging arms, and sliding feet tell the story of rhythmic movement, while a very loose and painterly atmosphere implies the movement of the air around the dancer's body.

Then, a few years ago, the need to produce a demonstration video on traditional, hand-drawn animation for some of my video students gave me an excuse to test the accuracy of my sketches.

While the 4 fps rate made the movement of the figure a bit more jerky in the finished video than would have occurred in a normal 15 fps animation, the relationship between the dancer and her music was, I think, conveyed in the 142 second/568 frame film.

But why don't I let the video speak for itself and you be the judge. What do you think?

And be sure to keep an eye on my new DrawntoAdventure YouTube channel for future postings of my brand new series of how-to, demo, and artist's materials review videos -- coming to a iPad or computer screen near you!

Labels:

animation,

Baroque,

Charles-Emile Reynaud,

demonstration,

flip book,

France,

hand-drawn,

Hellenistic,

movement,

Pauvre Pierrot,

stills,

stop-action,

zoetrope

Monday, August 20, 2012

How Art Helped Save A Post Office

Cynthia Nawalinski, Oregon

Everyone knows the United States Postal Service (USPS) has been experiencing rough times lately -- waining First Class customers, upper level management that was better at squandering financial resources on the sponsorship of totally unrelated cycling teams and Rose Bowl floats, a hostile Congress that imposes extraordinary regulatory burdens, and even the USPS’s own work force (who sometimes forget the meaning of customer service). With all this, and more, going against them it might seem that the postal service that was originally founded by Benjamin Franklin has become an obsolete anachronism in the modern digital age -- only good for stuffing our mailboxes with taxpayer-subsidized junk mail. But for some communities that couldn’t be farther from the truth.

In mid-2011, in an attempt to stem the flow of red ink, the management of the USPS compiled a list of 3,700 post offices which they had selected for possible closure. Now, if those post offices had been nondescript urban post offices in communities whose populations have easy access to high speed digital communication and are just a few miles of another post office branch, the public response might have been indifferent. But a large number of the post offices earmarked for termination were in rural communities, and many of those communities are still awaiting the arrival of fiber optics and the Digital Age. One of those communities was Stehekin, Washington.

Stehekin is a small, unincorporated township of just 85 year-round residents in central up-state Washington. Because of its location deep within the Cascade Mountain Range, the town has no radio or TV reception, and no cell phone service. It is also 50 miles from the nearest highway, grocery store, doctor’s office, or public library. In fact, Stehekin can only be reached by ferry, float plane, or on foot (via the Pacific Crest Trail). And yet, each year, thousands of visitors flock to this tiny little village. Why? Because Stehekin is the eastern gateway to North Cascades National Park and some of the most beautiful wilderness in the world. It’s also the last provisions point for “through hikers” on the Pacific Crest Trail (those intrepid adventurers who are completing the final stage of a hike from the Mexican border to the Canadian border).

And the post office? The Stehekin post office was established in May 1892 and was located in the Fields Hotel until 1927 and at “the Landing” since. Every household in the Stehekin River Valley has a post office box (there is no door-to-door service in Stehekin) where they receive letters and postcards from the outside world, library books and prescription medicines from the town of Chelan at the “down-lake” end of Lake Chelan. The post office also receives hundreds of parcels filled with the freeze-dried provisions through hikers will find essential for the final leg of their border-to-border trek (and ships out boxes filled with the excess gear hikers discover they can gladly do without on the trail).

Every day, the post master (the post office’s only employee) meets the mail boat with his hand cart to receive the in-coming mail, and each day he sees the boat off after seeing the out-going mail aboard -- summer or winter, rain or shine. (By comparison, UPS and FedEx packages are off-loaded onto the dock, where they are exposed to the elements till they are picked up by their recipients.)

Stehekin, however, is out of the ordinary for a community its size in having both a thriving artist community and its very own community art gallery -- located in the 85-year-old Golden West Visitors Center, which it shares with the National Park Service. And the artists community quickly banded together to draw public attention to the significance of their little post office, and to have fun at the same time. It was decided to host a mail art exhibition at the Golden West Gallery and to invite artists both near and far to participate.

Kate Foxglove, Texas

Kate Foxglove, Texas

After returning home from my artist’s residency with the National Park Service in the fall I was happy to use my internet and social network access to spread the word to others, who were kind enough to spread the word to even more creative folks. And the result was that, by the time the exhibition was installed in January, over 180 pieces of mail art had been received from 140 plus artists (including 1 pachyderm artist from Thailand!) on every continent except Antarctica -- and the final decision was made in Washington, D.C., not to close the post office!

So, if you ever take the ferry ride up the fjord-like lake and get to spend a few days taking in this beautiful wilderness gem of a community, be sure and take a bit of time to produce a watercolor postcard of one of the scenes and then walk it over to the post office. Buy a stamp from Jonathan (He always has a selection of the picturesque ones in stock.) Ask him to hand-cancel it. Then relax on the deck at the Landing Resort and watch as the mail bags depart on the afternoon mail boat. When you return home, you’ll find a very memorable one-of-a-kind keepsake of your visit awaiting you -- and the knowledge that you too may have helped save a post office!

getting a journal stamped at the post office

Author's Note: I'd like to extend special thanks to all of the artists who sent work in for the exhibition, Maps, Animals, Mountains, to Mark Scherer for providing the photos of the artwork, to the the Postal Service (both domestic and international) for getting the artwork to Stehekin safe and sound, and Jonathan Scherer -- quite possibly the friendliest postman I've ever met.

my postcard, from the Lone Star State

Letitia Lussier, Utah

Labels:

Australia,

exhibition,

France,

Indonesia,

mail art,

Oregon,

Pong the Elephant,

post office closures,

Russia,

Texas,

Thailand,

the Netherlands,

USPS,

Utah,

Washington state

Tuesday, August 14, 2012

Tools of the Trade #3 -- Toned Paper

watercolor, color pencils, and gold acrylic paint on Arches Cover buff

Paper -- without a doubt the most popular working surface for artists the world over. And, for most people, white is by far the most common color/tone of artist’s paper. However, ask anyone who has spent much time doing tonal drawings on white paper and they will certainly tell you that the majority of time involved in any drawing is spent getting rid of the white of the paper. But there is a faster alternative -- toned paper.

Pros --

Of course, we all know that in a tonal drawing we generally need three tones to convey volume and space -- light, dark, and middle tone. And we also know that the predominant tone in most drawings is middle tone. So, if we begin with middle tone before we even start drawing (i.e., in the paper itself) it stands to reason that the drawing will go much faster and that time tediously spent on white paper in hiding its “whiteness” can be focused on observation, rendering, and the creative process.

Con --

Since the majority of most artists‘ drawing experience has been with white paper, many of us have a tendency to “work from the tone of the paper (usually white) toward our darkest darks.” If this happens when working on toned paper we “overwork” the drawing. The tone of the paper ends up representing our highlights and we have once again drawn in both the middle and dark tones.

Solution --

First, begin with two mark-making tools instead of the usual one -- one light or white, and one dark or black.

toned papers come in a wide range of colors, values & temperatures, and your light/dark tools can be pencils, pens, crayons, pastels, or paints - there's something for everyone

Next, using your dark or black drawing instrument, carefully draw the outline of your subject. (Using a light pressure will make it easier to erase any errors at this stage and reserves the boldest, darkest darks for the end of the drawing, when your observational focus is usually keenest.)

Now (and THIS is where drawing on toned paper departs from the routine you may have developed working on white paper), put down your dark pencil or pen! Switch to you white/light mark-maker (pen, pencil, crayon, etc.) and begin placing your highlights, working from those areas that most closely resemble the middle tone of the paper toward the brightest highlights -- again, saving the boldest marks (which are generally the hardest to erase) until the end (when your observations are normally most focused and most accurate.)

Once you have “mapped out” the highlights with a light-pressured mark from your white pencil you can begin alternating between your light and dark mark-makers -- gradually moving from the tone of the paper toward both your lightest lights and darkest darks -- with greater confidence that you will not “overwork” your drawing.

Sakura Pigma color pens, watercolor & Prismacolor pencils

Important Technical Tip -- DON'T blend your light with your dark! Mixing the two produces middle tones and, of course, middle tones are your paper’s responsibility. (If you’re mixing middle tones, your overworking your drawing.)

Where to Begin --

OK, you’ve read my article, you’re intrigued (I hope), and you want to give it a try. So, your next question is likely, “What paper do I use?” Fortunately, there are several brands available and I’ll share three of my personal favorites with you today (and one to be avoided.)

First, the paper type to be avoided, DON’T buy that brightly colored construction paper sold by the ream. It doesn’t have enough sizing to make the surface very receptive to most drawing media. It’s not archival. (In fact, to reduce the cost of manufacturing, this paper may actually be acidic.) And the dyes used to color the paper are usually fugitive and will fade rapidly with exposure to most light sources.

Prismacolor pencils on Arches Cover black paper

For many of us, the most readily available professional quality toned paper will be the exceptional line manufactured by the Canson Paper Company at paper mills that have been located in Annonay, France, since 1557. Canson papers come in two weights -- the heavier Mi Teintes line (with one smooth side, and one mechanically “dimpled” side to give you a choice of working surfaces), and the lighter Ingres line (developed for, and named after, the artist Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres) with it’s pronounced, and much duplicated, chain or laid pattern (which it picks up from the screen during the paper-making process.) Even their muted earth-toned papers sparkle due to the presence of small brightly colored fibers dispersed throughout the gray or tanned sheets.

pen & ink with ink wash and acrylic highlights on Canson Mi Teintes Moonstone paper

Ebony pencil, watercolor to create pictorial space, and a little white color pencil on a warmer Canson Mi Teintes

Another fine line of professional quality toned papers are made by the Italian firm Fabriano, which has been in operation since the late 13th century and include no less than Michelangelo Buonarroti among their satisfied artist customers. While perhaps not as universally available as their French counterpart, Fabriano’s Tiziano line of colored papers are particularly renowned for the use of fade-resistant pigments (instead of more fugitive dyes) as coloring agents and are definitely worth trying.

pen & ink with color pencils on Fabriano Tiziano paper

B&W color pencil over pen & ink on Fabriano Ingres paper

watercolor over Sakura Micron Pigma color pens on Fabriano Ingres paper

I take a little liberty as the "third company" in my list isn’t a company at all but a separate (and VERY special) range of papers manufactured by Fabriano -- the Roma line. Roma is unique because it is handmade, heavily sized (hold a sheet by one corner and shake it -- it will rumble like thunder!), with four deckled edges, a pronounced Laid texture imparted by the paper-making screens, and a huge watermark. This remarkable paper is a delight to draw on with pencil, pen, color pencil, or brush. It can be used as stand-alone sheets or crafted into unique, one-of-a-kind books. And (unfortunately), due to its being hand-made, it is the most expensive paper I use ($13.60 from New York Central Art Supplies.)

quarter sheet of Fabriano Roma backlit to show screen pattern and watermark

watermark closeup

fude brush pen, watercolor, white highlight, and Chinese vermilion on Roma paper

OK, I’ll admit that Roma is not a paper most of us are going to rush out and stock up on. In fact, it can be downright hard to find at times. So, in fairness (and to avoid getting lynched) I’ll add one other company and two toned paper lines to the list. The company is Magnani (which has been hand-crafting premium quality papers since the 15th century and has built a reputation for producing unique paper products for illustrious customers -- from Napoleon Bonaparte to the Bank of Italy), and the papers are Firenze (hmm, do I sense an inter-city rivalry here?) and Pescia. The hand-made Firenza has many of the attributes of Fabriano Roma plus a velvety surface and an ever-so-slightly-less-shocking price tag. But don’t let me fool you. Hand-made papers are labor-intensive and are made by highly skilled laborers. That can’t come cheap -- unless you learn to make your own (or marry someone who will make paper for you. ;-D)

And the Pescia? There are five colors in this paper range, but the only one I regularly use is their unique (and truly beautiful!) pale blue. Originally developed as a printmaking paper, Pescia is a “waterleaf” (i.e., no sizing.) So, don’t use watercolor or ink washes on this paper. But, when used with Prismacolor Indigo and white color pencils, this paper is a one-of-a-kind delight to work with.

Should you decide that you want to explore the creative potential of toned paper, don't be hesitant to experiment. Can't find a stockist in your community? Think about making your own paper. Your local art supply shop doesn't have the color that's right for you? Try toning your own paper. (Hot Press watercolor blocks are perfect for this, by the way. And the toning wash will raise the tooth of the paper ever so slightly -- which I find enhances its drawing quality.) Working on a tight budget? That's not a problem. That's "the Mother of Invention"!

Should you decide that you want to explore the creative potential of toned paper, don't be hesitant to experiment. Can't find a stockist in your community? Think about making your own paper. Your local art supply shop doesn't have the color that's right for you? Try toning your own paper. (Hot Press watercolor blocks are perfect for this, by the way. And the toning wash will raise the tooth of the paper ever so slightly -- which I find enhances its drawing quality.) Working on a tight budget? That's not a problem. That's "the Mother of Invention"!

hand-made paper (the color and texture options here are limitless)

Here are four examples of toned paper which may convey some of the creative options you might want to explore. The pale blue is the Magnani Pescia mentioned earlier. The sheet on top of the Pescia is Arches HP watercolor paper that was toned with strongly brewed tea. (I favor PG Tips or Trader Joe's Irish Breakfast.) The next paper up is another piece of Fabriano Roma -- this one was one of their creme-colored sheets before I poured tea on it too. (Notice that different papers will react differently to the same toning agent. Bottom line: experiment!) And the final sheet is another piece of HP watercolor paper that was first toned a pale tan and then spackled with thinned acrylic ink.

extreme close-up of the toned and spackled w/c sheet (magnified larger than life to make it easier to convey here)

Well, hopefully I’ve wet your artistic appetite for the creative possibilities of toned paper and given you a few more options for ways to further deplete your bank account (like any artist has a shortage of those! ;-D) So, now all you have to do is run down to your local art supply shop and pick up a few sheets of Canson Mi Teintes in the color(s) of your choice. If that's not practical, or if you don't like the color choices, not to worry. You can create your own toned paper by mixing up the color of your choosing in water-based paints (watercolor if you will be working in pencil or pen & ink, a very fluid acrylic if you in ten to overpaint with ink or watercolor washes) and using it to "stain" a sheet of Hot Press watercolor paper.

paper scraps can be a great excuse for experimentation. here it's a new apricot-colored toning on HP w/c paper, silverpoint (with silver wire in a vintage mechanical pencil) and gouache highlights. the results are delightfully subtle (though perhaps a bit difficult to convey digitally)

toned paper can be an excellent alternative to the usual white paper in nature

studies field work, frequently producing much bolder results in far less time

So, ladies and gentlemen, let the fun begin!

A Very Brief History of Paper --

Even in the Digital Age we still have a long way to go to become a “Paperless World” -- paper is everywhere. And (thankfully) it’s part of our daily life. But, in the west, it wasn’t always so. In early times wet clay tablets were frequently used to permanently record information. The fibers of a water plant called papyrus was soaked, beaten flat, and woven into thin mats, which -- when dry -- could be written or drawn on. And for centuries the prepared skins of goats (parchment) and calves (vellum) were the predominant surface for writing and drawing. (In fact, so valued were parchment and vellum that it was fairly common during the Middle Ages for writers of one era to scrape away the words of earlier writer’s in order to “recycle” a book structure.)

The Chinese revolutionized writing, printing, art-making (and, no doubt, the lives of untold numbers of future bureaucrats, bean couters, and other “paper shufflers”) in the early 2nd century AD with the invention of the modern paper-making process. And Cai Lun produced the earliest known illustrated guide to the “five seminal steps” of paper-making in 105 AD.

First paper and then paper-making made its way along the Silk Road to Samarkand, Baghdad, and Damascus. There Arab papermakers further refined the paper-making process. And, during the Crusades, at least one Christian (Jean Montgolfier) learned the paper-making techniques as a POW in Damascus -- techniques he took home to France after his release, and used to establish what is known today as the Canson Paper Mill.

Even so, for nearly three centuries, European law prohibited the use of paper for permanent records (vellum and parchment were stipulated) because the wheat paste sizing commonly used resulted in a rapid deterioration of the paper. It wasn’t until paper mills began using animal-based sizing during the Renaissance that the laws were finally changed -- and paper finally entered the lexicon of artists‘ materials.

An interesting little side note to end this week’s article with -- two of Jean Montgolfier’s descendants used paper produced by the family’s mill to coat the inside of a fabric bag (rendering the fabric airtight.) This sac was, in turn, filled with hot air, the hot air balloon flight in history was made, and the Age of Flight was born. (As a flight instructor, I shared the history of the Montgolfiers with my students for ten years. But it was years later before I learned that paper had been involved, and of the Canson Paper Mill connection.)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)